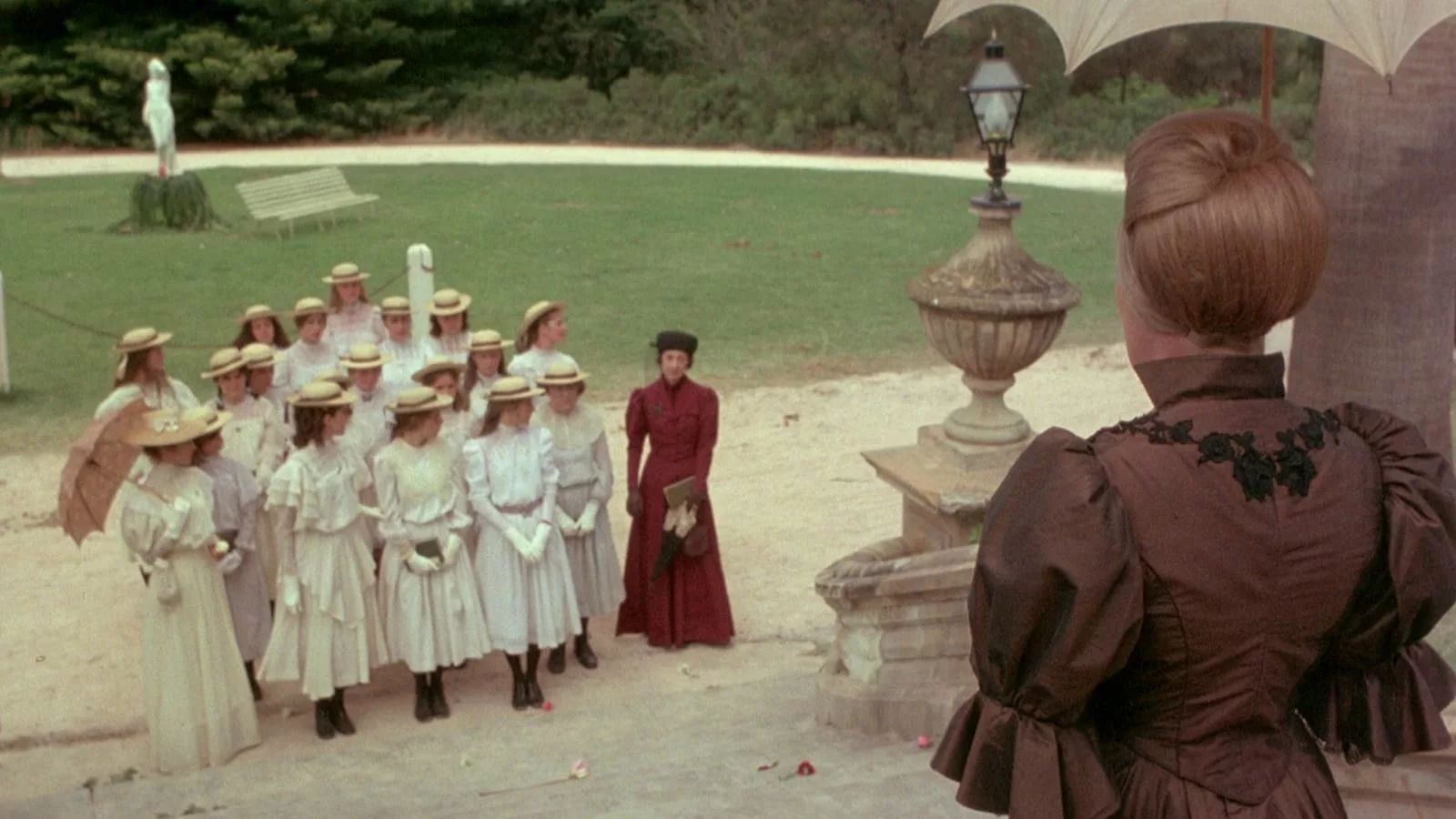

There’s something about “Picnic at Hanging Rock” that makes one obsessive. Directed by Peter Weir and based on the novel of the same name by Joan Lindsay, the film takes place in 1900 and charts the aftermath of the disappearance of three schoolgirls and a teacher during a Valentine’s Day picnic beneath Hanging Rock, a towering and abrupt shard of volcanic rock in Victoria, Australia. About a million years old, it was created when “siliceous lava forced up from deep down below,” says Miss McCraw, the teacher who ends up missing, as the group of students from Appleyard College rides up to the site: “Soda trachytes extruded in a highly viscous state, building the steep-sided mametons we see in Hanging Rock.” Despite this knowledge of the rock, extant in precise scientific terms, it manages to swallow Miss McCraw and a couple of the girls and secrets them somewhere no search party nor bloodhound’s questing nose can find. The mystery of the disappearance confounds the local community, throwing the girls’ school into chaos.

The mystery begins when four girls break away from the larger group to go and explore the landmass. Only one immediately returns, in hysterics after having watched the other three remove their stockings and move higher up into the rock. Upon the remaining girls’ return to Appleyard, we learn that Miss McCraw has also disappeared, after having walked toward Hanging Rock in nothing but her bloomers. The girls and their teacher are never found, save for one, who is discovered concussed a week later. She does not regain memory of what happened.

One watches the film with bated breath, viscerally enthralled by the mystery laid out, but no answer or explanation is ultimately provided, and as the credits roll, our lungs ache for air, for a sigh of relief. One finds oneself trying to piece together a satisfying answer to the disappearance long after having seen the film. Writer Megan Abbott says that critics in 1975 called the film “unsatisfying” or “frustrating,” and quotes Weir in describing an industry screening where a distributor “threw his coffee cup at the screen at the end … because he’d wasted two hours of his life—a mystery without a solution!” This dissatisfaction at the lack of a solution wasn’t unique to the film, either. Roger Ebert notes in his review of the film that when Lindsay published the novel in 1967, she suggested it was based on fact: “A cottage industry grew up in Australia about the novel and the movie; old newspapers and other records were searched without success for reports of disappearing schoolgirls.” It was like an itch you couldn’t scratch, or an unsatisfying and shallow gasp for air. Like the townsfolk in the film, everyone desperately wanted to figure out the mystery of the women’s disappearance.

But the film doesn’t seem to care about our discomfort—rather, it stokes it: “That frustration, however—the unsettling, provocative sense of hidden truths withheld from us—is integral to the film itself, and one of its greatest powers,” writes Abbott. For Abbott, the film’s project is to have us confront the act of looking, both on the part of the characters in the film and us as viewers, and to consider the part the viewer has in crafting a story around the young women in the film. As we watch the film, Abbott says, we focus on the clues that fit into our distinct understanding of the world or support our theory in order to lay out a coherent narrative. We focus on whatever supports our “fantasies that the girls have been, alternately, raped and murdered, abducted by aliens, whisked away by the ‘Aboriginal Other’ à la colonial melodrama, or swept up in a holy rapture.” But we never find the actual solution, none of our theories are ever confirmed, and we’re left with ourselves. “By not providing a ‘solution,’ the film leaves us face-to-face with our own self-generated projections, our shameful fantasies. Any dark, unseemly, or erotic scenario we imagine in our heads, we must acknowledge as our own,” says Abbott.

I would add to Abbott’s theory that our discomfort or frustration with the film’s lack of solution is itself gendered: our desire for a strict theory as to what happened to the girls and their teacher, as opposed to satisfaction with the frayed and hazy maze of gossip and “seemings,” is a desire baked into us by our patriarchal culture. When this desire is not satisfied by the film and we confront our work at narrativizing or rationalizing, the discomfort we feel at the missing puzzle pieces stems from an unease with the monstrous feminine that is passed down to us through our cultural stories, through our patriarchal society.

After the girls and Miss McCraw have disappeared, the police and community embark on a thorough search of the bush, to no avail. The constable, home after a long and fruitless day, sits dejected before his wife. “People just don’t disappear, my dear,” she says. “Not without good reason.” When the constable asks if there has been speculation amongst the townsfolk about what might have happened, the wife raises her brows. “Not just gossip,” she says, making a clear distinction. “People have theories.” And she then embarks on a sequence of premises, rational argumentation—ideas not simply about what could have happened, but what was likely to have happened according to probability, to mathematics, to science. The constable’s wife articulates not only the town’s thinking process, but ours, too, bringing to light the rationalizing work our fantasies, as Abbott calls them, are doing as we watch the film. According to the laws of physics and geology and sociology, what is likely to have happened? we wonder. And this wondering on the town’s part and on our part is an attempt to fit the events of the film into the confines of reason, which has long been codified as masculine by our culture.

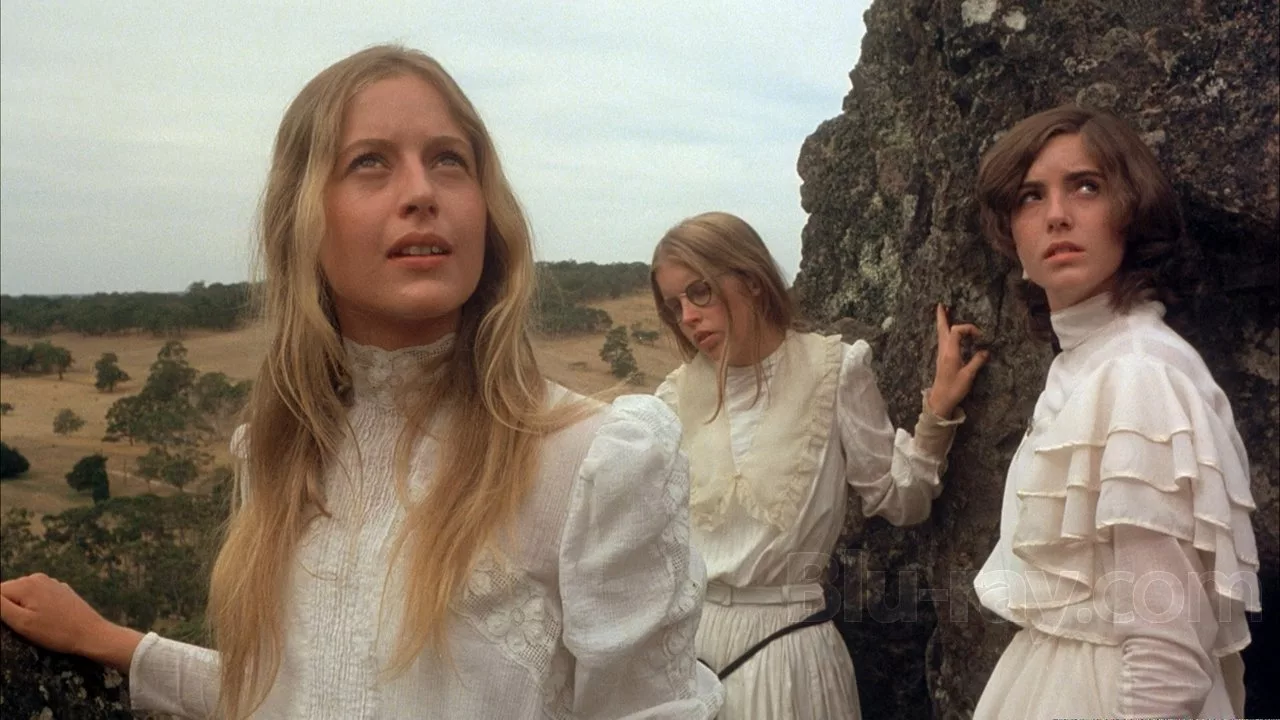

But nothing about the disappearances seems amenable to logic. As the girls explore the rock, it doesn’t seem as though they’re moving on it in a linear (distance-wise) fashion. Rather, they move from crevice to crevice without any indication of where they might be height-wise, how high up or low to the ground, whether they are going forwards or backwards: we catch glimpses of them through spaces in the rock that from a distance seems one solid piece, and as they move into it, it seems as though it is endlessly folding into itself, with an endless amount of tunnels and burrows and archways. When they take a break to nap, it seems as though they have reached the summit, but then three of them climb yet higher, and when they do, they’re as if in a daze. They remove their shoes and their stockings, and Irma, the only girl to be found, also loses her corset at some point. As the three girls shed layers, their movements are wordlessly in sync, as if following some silent direction, as if under the sway of some divine or sublime force. And then they disappear around another corner. Hanging Rock, a formation that has been mapped and catalogued in excruciating detail, is as if a space without any contours when the girls explore it—its height ever expanding, crevices endlessly appearing. Something so clearly defined as a geological entity becomes an inscrutable and alive and changing thing.

It is noteworthy that the girls go to the rock to gather its measurements—at least, that’s what they say. Earlier in the afternoon, before the girls leave, it is discovered by the driver Ben Hussey that their watches stopped. Miss McCraw is reading a book on mathematics right before she disappears. As Weir’s lens hovers above her, we see that she is reading a chapter called “Heights and Distances,” and illustrated on the page is a strong and reliable triangle.

Mrs. Appleyard is the school’s headmistress, raised on the rigors of patriarchal society and staunchly devoted to upholding Victorian patriarchal morality literally under the gaze of Queen Victoria (the lens lingers often on the Queen’s painting, her judgemental and pinched eyes). She says, “I came to depend so much on Greta McCraw. So much masculine intellect. How could she allow herself to be spirited away? Lost. Raped. Murdered in cold blood like a silly schoolgirl on that wretched Hanging Rock.” In other words, how could Miss McCraw allow herself to abandon her masculine reason and lapse into amorphous femininity, the kind of hazy spiritualism that has the girls dance like pagans on the rock shortly before they disappear into it. Miss McCraw literally sheds her rationality—she abandons her watch, her book, her clothes, and moves up and away into the mountain. Into the mystery of the wilderness.

Hanging Rock defies reason and measurement, it is governed by something mysterious, something magical, it is ancient earth, it is cavernous, its beds are the source like a womb for life, it is moist and dark, and it is where women take their shoes and corsets off and disappear. Hanging Rock is feminine disorder, the site where the civility of society—the rule of Victoria’s patriarchal, colonial community—holds no sway or power, where order is meaningless and no questions find answers. And “Picnic at Hanging Rock” charts a community’s deep and abiding discomfort with the disorder of Hanging Rock, of unruly nature, of the monstrous feminine. Weir ultimately shows us that, in the way that corsets never contain a woman’s curiosity, no amount of theories will be enough to capture the vastness and elasticity of the earth.

The film exposes the patriarchal and colonial desire to demystify the monstrous feminine and thereby control it or tame it. Theories abound, as the constable’s wife says, theories that are crucially not something as indefinite as feminine-coded gossip. The town is rife with a desire to bore into the girls’ minds, into Miss McCraw’s mind, to further map out Hanging Rock, all in an effort to lay its rational premises in order, to determine definitely what happened and solve the mystery.

But what do we get when we solve the mystery? A feeling of unease, says a film like Joel Anderson’s “Lake Mungo,” which follows a similar mystery linked to the Australian bush. The film’s pivotal event,[MS1] the death of a 16-year-old girl named Alice Palmer, takes place in 2005, 30 years after “Picnic.” “Lake Mungo” is a faux documentary that follows a family’s attempt to understand Alice’s mysterious drowning—the girl was deeply troubled in the months leading up to her death, especially after a school trip to a campsite on Lake Mungo, an ancient, dried-up lake. There, she saw an omen of her own death. When the Palmers, who throughout the film are working to put logical meaning behind the girl’s abrupt and illogical death, learn ultimately that Alice was deeply distraught after having encountered a vision of her own death, they find a certain peace, because they feel they have an answer. For the Palmers, it makes sense that Alice should die at 16 if she was emotionally upset, because this is an ultimate cause, and rational thinking loves ultimate causes. But the film ends on a series of unsettling images: a hazy and transparent image of Alice can be seen in the margins of photographs the Palmers took. It’s her ghost and she stills lingers despite the circular logic that the Palmers have found refuge in. How can the Palmers find happiness if Alice’s ghost is still on this plane? It’s a deeply dissatisfying note for the film to end on. The film shows that despite a desperate search for meaning, there are loose ends, there is sadness, there is still a ghost, lingering in the air like the spiritual force that drives the girls up Hanging Rock.

“Lake Mungo,” like its direct inspiration “Twin Peaks,” is working in the tradition that “Picnic” established, and one that is apparent in a host of horror films—like “The Exorcist” and “The Entity”—which not only depict a friction between reason and the monstrous or mysterious feminine, but also point to reason’s shortcomings. Most recently, Teresa Sutherland’s “Lovely, Dark, and Deep” interrogated the need for reason. The film, following a park ranger trying to understand why people keep going missing in a national park, almost seems to abandon reason by its end, favoring the irrationality of cavernous horror. We never get an explanation of what is really going on with the park—no geology or archeology or scientific theory—only the fact that something strange is happening, and one must let it happen. By the end of the film, Sutherland almost privileges the monstrous feminine, the inexplicability of nature and its deep and dark wells. It’s a frustrating movie, but that is not where its heft lies. Sutherland has baked meaning into the film’s emotional landscape, and though we might leave the film confused, we also leave with our hearts feeling full, for we made visceral contact. This is a lesson the film seems to have picked up spiritually from Weir.

Fifty years after its release, “Picnic at Hanging Rock” is just as poignant as it was when it had coffee thrown at it. It is just as captivating not only because of its privileging of the monstrous feminine in all her unruly beauty, but also in its ability to sow a doubt in our bellies about the efficacy of reason, having us confront why we want to stamp cold, hard theories onto something so beautiful as this film. Weir’s film is full of secrets and mystery, but it is also alive with magic.